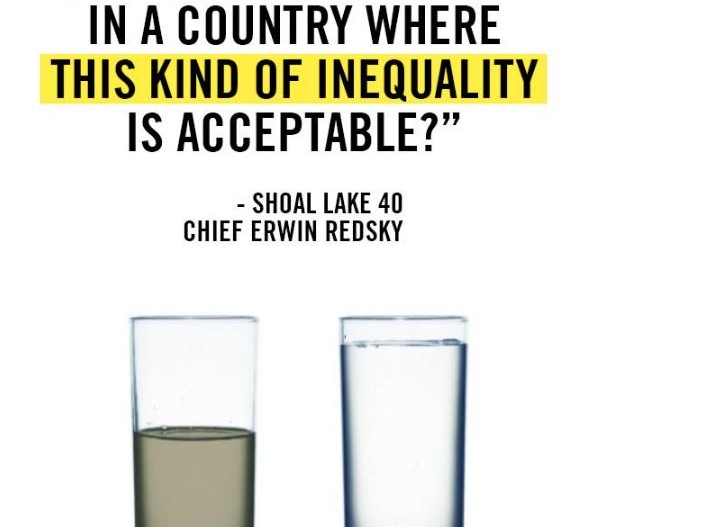

OTTAWA — The federal government will not meet its commitment to end all drinking water advisories affecting First Nations communities by 2020 without significant changes to current processes, according to a new report, Glass half empty? Year 1 progress toward resolving drinking water advisories in nine First Nations in Ontario.

Released by the David Suzuki Foundation and Council of Canadians, and with advisers Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, the report assesses the federal government’s progress in nine First Nations across Ontario. With 81 active DWAs — more than any other province — Ontario provides a snapshot of Canada’s First Nations water crisis.

“We are calling on the government to work with First Nations to make necessary changes to the way it addresses the lack of safe drinking water in First Nation communities,” said David Suzuki Foundation Ontario science projects manager Rachel Plotkin. “At present, it is not on track to meet its promise.”

As of last fall, Canada had 156 drinking water advisories affecting 110 First Nations communities, many of which are recurring or ongoing. Some have been in place for more than 20 years. The 2016 federal budget included $1.8 billion to help resolve the crisis by 2020, in addition to funding it has already invested in First Nations water infrastructure, operations and management.

Of the nine First Nations profiled in the report, three are on track to or have had drinking water advisories lifted; efforts are underway in three others, but there is uncertainty about whether the advisories will be lifted on time; and for the remaining three, it is unlikely advisories will be lifted by 2020 unless current processes and procedures are reformed. One community that had its DWA lifted now faces a new suite of problems, pointing to the need for long-term, sustainable solutions.

The report reveals fundamental flaws in how the federal government fulfils its responsibility to ensure safe drinking water in First Nations communities. These include a highly complex funding process full of loopholes, gaps and delays; a lack of transparency and accountability in federal monitoring of progress; and the lack of a regulatory framework to govern drinking water for First Nations.

The report outlines a series of 12 recommendations that the government must implement to get its work back on track.

“Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada not only needs a new system for fixing water infrastructure; it needs a new system of accountability, so First Nations and the general public can track how the budget is being spent and what progress is being made,” Plotkin said.

“The Canadian government is required to implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and recognize human rights to water and sanitation, but it has yet to take the action required to uphold these rights,” said Council of Canadians political director Brent Patterson. “This report’s recommendations are long overdue steps that the government must take to ensure these fundamental rights are enjoyed by all people in Canada.”

“This report highlights the need for a more transparent process for how long-term drinking water advisories will be addressed, so that First Nations and Canadians can monitor the government’s progress toward its commitment and, ultimately, toward the realization of the human right to water for First Nations,” said Amanda Klasing of Human Rights Watch.

The complete Glass half empty? report is available at davidsuzuki.org/water.

-30-

For more information or to arrange an interview, please contact:

Brendan Glauser

Communications Manager, David Suzuki Foundation

(604) 356-8829

bglauser@davidsuzuki.org

Note to editors:

In addition to the full report and news release, the following materials are available to all media:

● Infographics

● Fact sheet