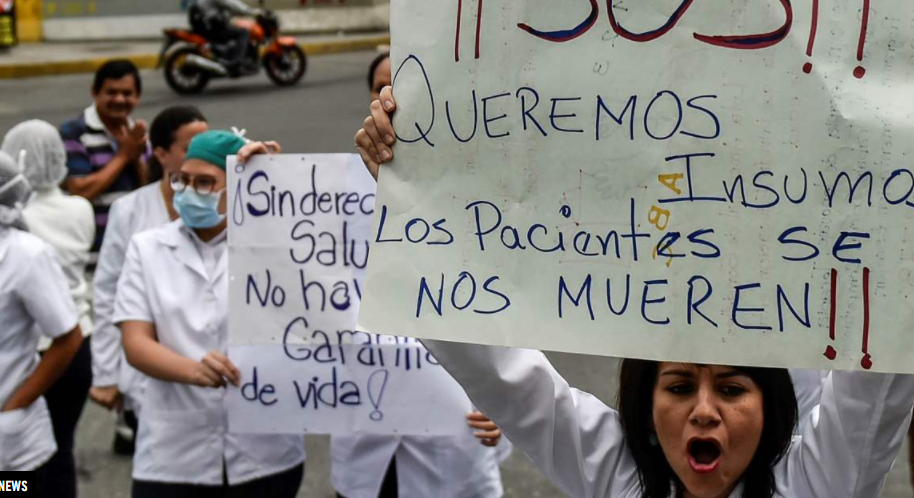

As the daily number of COVID-19 cases reported in Venezuela has accelerated at the quickest rate yet in recent weeks, authorities are failing to take action to protect the population and, in particular, the doctors, nurses and hospital and clinic workers who are being sorely hit, and even jailing those who speak out about their dire labour conditions, said Amnesty International today.

“The Venezuelan authorities are either in denial about the number of health workers to have died from COVID-19, or they do not have accurate information about the precarious conditions in hospitals and the dire need for better protection of staff and patients alike. Either way, the government is being utterly irresponsible,” said Erika Guevara-Rosas, Americas director at Amnesty International.

“While the Nicolás Maduro government has called on the population to applaud health workers in recent weeks, what they really need is not clapping, but concrete government action to procure the resources they need to work in safety, and allow their voices to be heard without reprisals.”

According to the organization Medicos Unidos de Venezuela, 71 health workers died from 1 July to 16 August, with 37 of those deaths coming in just the first 16 days of August. This total represents almost 30% of the total deaths reported by authorities from COVID-19 in Venezuela which stand at 288. However, authorities are failing to disaggregate deaths by sector and many deaths of health workers are not being counted in the official register.

Amnesty International gathered information indicating that on 16 August there were 691 patients hospitalized for symptoms of COVID-19 in the main hospitals of the city of Caracas alone. This raises doubts about the veracity of the official daily numbers of cases across the country, with authorities reporting just 1,148 new cases of COVID-19 across the entire country on 16 August.

Venezuela stands out as a stark example of state reprisals against health workers. Since Amnesty International began monitoring the situation of health workers across the Americas in early April, Venezuela is the only country that has gone so far as to jail those who have spoken out publicly about risks to their safety and that of patients.

While reprisals against health workers who act as whistle-blowers have occurred in many countries of the region, to Amnesty International’s knowledge, Venezuela is the only country in the region that has arrested health workers and brought them before military and civil tribunals. To date, Amnesty International had received information of at least 12 health workers who have been detained during the pandemic, including many whose due process was violated as they were not informed of the charges against them. Amnesty International has reported for years now the policy of repression implemented by Maduro’s government to silence and control the population which includes arbitrary detentions and torture to a wide range of people who have raised their voices.

In recent years, approximately 50 per cent of the country’s doctors have left the country, according to the Venezuelan Medical Federation (FMV), leaving Venezuela with scarce human resources to face the pandemic. The exit of so many medical personnel comes in the context of the humanitarian emergency and human rights crisis that has seen 5.2 million flee the country.

The health workers who stayed in Venezuela earn between 4 and 18 USD a month, and many have had to walk to work, sometimes for over 10 km, as they cannot afford transport. According to the civil society watchdog Monitor Salud, 68% of 296 health workers surveyed in Caracas from March to June arrived at work without any food in their stomach before starting an arduous shift. The average living expenses of groceries and basic utilities per month for each Venezuelan are estimated at USD 513, according to the national research organization CENDAS.

Venezuelan labour law states that workers should be protected from risks at work, but according to the local NGO PROVEA, workers are being left completely exposed without personal protective equipment (PPE). In the small number of cases where workers are supplied with PPE, they are being forced to re-use masks for prolonged periods of time, making them ineffective. There have also been alarming reports of government delegates assigned to certain states visiting hospitals cloaked in full protective gear, when health workers have been left with very little equipment.

In mid-July, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) donated 20 tonnes of PPE for 31 hospitals across the country. While this is an important contribution to protecting Venezuela’s health workers, there are 240 hospitals throughout the country and authorities have the responsibility to ensure protective equipment for all hospitals. In addition, hospital staff from the states where the PAHO donations were said to have been delivered reported no change in their daily working conditions after donations arrived in the country. It is imperative that civil society groups have more precise information on these humanitarian donations, in order to activate an independent monitoring mechanism to ensure that aid is arriving where it is most needed.

The Venezuelan government must do more to properly diagnose and assess the country’s need for international cooperation in the form of donations, as well as taking concerted efforts to re-assign resources to ensure health workers have access to gloves, surgical gowns and masks. The government must also ensure that there are sufficient cleaning products and disinfectant in hospitals. Close to half of the country’s hospitals have no water or shortages of water, and according to workers organizations, many of them have not been properly disinfected once during the pandemic.

For more information or to arrange an interview, please contact Lucy Scholey, Media Relations, Amnesty International Canada (English branch), 613-744-7667 ext. 236, lscholey@amnesty.ca

Read more:

The cost of curing: Health workers’ rights in the Americas during COVID-19 and beyond (Research, 19 May 2020) https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/amr01/2311/2020/en/